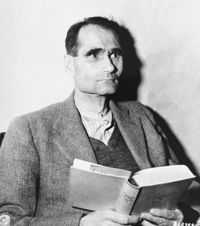

Rudolf Hess

- Not to be confused with Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp

| Rudolf Hess | |

|

|

|

Stellvertreter des Führers

Deputy Führer |

|

| In office 21 April 1933 – 12 May 1941 |

|

| Preceded by | Post created |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Martin Bormann (As Chief of the Parteikanzlei) |

| Lieutenant | Karl Gerland Martin Bormann |

|

|

|

| Born | 26 April 1894 Alexandria, Khedivate of Egypt Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 17 August 1987 (aged 93) Spandau, West Berlin Allied Occupied Berlin |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) (Since 1920) |

| Spouse(s) | Ilse Pröhl (22 June 1900 - 7 September 1995) married 20 December 1927 |

| Children | Wolf Rüdiger Hess (18 November 1937 - 14 October 2001) |

| Alma mater | University of Munich |

| Profession | Reichsminister |

| Signature | |

| German spelling is Heß | |

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (written Heß in German) (26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a convicted Nazi war criminal acting as Adolf Hitler's Deputy in the Nazi Party. On the eve of war with the Soviet Union, he flew solo to Scotland in an attempt to negotiate peace with the United Kingdom, but instead was arrested. He was tried at Nuremberg and sentenced to life in prison at Spandau Prison, Berlin, where he died in 1987.

Hess' attempt to negotiate peace and subsequent lifelong imprisonment have given rise to many theories about his motivation for flying to Scotland, and conspiracy theories about why he remained imprisoned alone at Spandau, long after all other convicts had been released. On 27 September and 28 September 2007, numerous British news services published descriptions of conflict between his Western and Soviet captors over his treatment and how the Soviet captors were steadfast in denying repeated entreaties for his release on humanitarian grounds during his last years.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Hess has become a figure of veneration among neo-Nazis.[7][8][9] His son Wolf Rüdiger Hess became a prominent rightist and claimed that his father was murdered.

Contents |

Biography

Early life

Hess was born in Alexandria, Egypt, the eldest of four children, to Fritz H. Hess, a German Lutheran importer/exporter from Bavaria and Klara Münch. The family moved to Germany in 1908, where Rudolf was subsequently enrolled in boarding school. Although he expressed interest in being an astronomer, his father convinced him to study business in Switzerland. At the outbreak of World War I he enlisted in the 7th Bavarian Field Artillery Regiment, became an infantryman and was awarded the Iron Cross, second class. After being wounded on numerous occasions — including a chest wound severe enough to prevent his return to the front as an infantryman — he transferred to the Imperial Air Corps (after being rejected once). He then took aeronautical training and served in an operational squadron, Jasta 35b (Bavarian), with the rank of lieutenant from 16 October 1918. He won no victories.

On 20 December 1927 Hess married 27-year-old Ilse Pröhl (22 June 1900 – 7 September 1995) from Hannover. Together they had a son, Wolf Rüdiger Hess (18 November 1937 – 24 October 2001).

Hitler's deputy

After the war Hess went to Munich and joined the Freikorps and Eiserne Faust (Iron Fist).[10] He also joined the Thule Society, a völkisch occult-mystical organization.[11] Hess enrolled in the University of Munich where he studied political science, history, economics, and geopolitics under Professor Karl Haushofer. After hearing Hitler speak in May 1920, he became completely devoted to him. Ilse Hess’ description of the results of her husband’s first encounter with Hitler is reminiscent of a religious conversion.[12] For commanding an SA battalion during the Beer Hall Putsch, Hess served seven-and-a-half months in Landsberg Prison. Acting as Hitler's private secretary, he transcribed and partially edited Hitler's book Mein Kampf. He also introduced Hitler at party rallies. Eventually, Hess became the third-most powerful man in Germany, behind Hitler and Hermann Göring.

Soon after Hitler assumed dictatorial powers, Hess was named "Deputy to the Fuhrer." Hess had a privileged position as Hitler's deputy in the early years of the Nazi movement and in the early years of the Third Reich. For instance, he had the power to take "merciless action" against any defendant who he thought got off too lightly — especially in cases of those found guilty of attacking the party, Hitler or the state. Hess also played a prominent part in the creation of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935. Hitler biographer John Toland described Hess' political insight and abilities as somewhat limited.

Hess was increasingly marginalized throughout the 1930s as foreign policy took greater prominence. His alienation increased during the early years of the war, as attention and glory were focused on military leaders, along with Göring, Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler. Hess worshipped Hitler more than the others, but he was not nakedly ambitious and did not crave power in the same manner they did. However, as the Deputy Fuhrer, Hess held as much power (If not more than) the other Nazi leaders under Hitler. He controlled who could get an audience with the Fuhrer, as well as passing and vetoing proposed bills, and managing party activities. [13]

On the day Germany invaded Poland and launched World War II, Hitler announced that should anything happen to both him and Göring, Hess would be next in the line of succession.[14]

Hess ordered a mapping of all the ley lines in the Third Reich.[15]

Flight to Scotland

Like Goebbels, Hess was privately distressed by the war with the United Kingdom because he, like almost all other Nazis, hoped that Britain would accept Germany as an ally. Hess may have hoped to score a diplomatic victory by sealing a peace between the Third Reich and Britain,[16] e.g., by implementing the behind-the-scenes move of the Haushofers in Nazi Germany to contact Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton.[17]

On 10 May 1941, at about 6:00 P.M., Hess took off from Augsburg in a Messerschmitt Bf 110, and Hitler ordered the General of the Fighter Arm to stop him (squadron leaders were ordered to scramble only one or two fighters, since Hess' particular aircraft could not be distinguished from others).[18] Hess parachuted over Renfrewshire, Scotland on 10 May and landed (breaking his ankle) at Floors Farm near Eaglesham. In a newsreel clip, farmhand David McLean claims to have arrested Hess with his pitchfork.[18]

It appears that Hess believed the Duke of Hamilton to be an opponent of Winston Churchill, whom he held responsible for the outbreak of the war. His proposal of peace included returning all the western European countries conquered by Germany to their own national governments, but German police would remain in position. Germany would also pay back the cost of rebuilding these countries. In return, Britain would have to support the war against the Soviet Union.

Churchill sent Hess initially to the Tower of London, making Hess the last, in the long line of prominent political prisoners, to be held in the fortress.[19] Churchill gave orders that Hess was to be strictly isolated, but treated with dignity.[20] He remained in the Tower until 20 May 1941.

After being held in the Maryhill army barracks, he was transferred to Mytchett Place near Aldershot. The house was fitted with microphones and sound recording equipment. Frank Foley and two other MI6 officers were given the job of debriefing Hess — or "Jonathan", as he was now known. Churchill's instructions were that Hess should be strictly isolated, and that every effort should be taken to get any information out of him that might be useful.[21] British Intelligence personnel, Ian Fleming in particular,[22] proposed that Aleister Crowley should question Hess on Nazi interest in the occult.[23]

Hess became increasingly agitated as his conviction grew that he would be murdered. Mealtimes were difficult, since Hess suspected that his food might be poisoned, and the MI6 officers had to exchange their food with his to reassure him. Gradually, their conviction grew that Hess was insane.

Hess was interviewed by psychiatrist John Rawlings Rees, who had worked at the Tavistock Clinic prior to becoming a Brigadier in the British Army. Rees concluded that he was not insane, but certainly mentally ill and suffering from depression — probably due to the failure of his mission.[21] Hess' diaries from his imprisonment in Britain after 1941 make many references to visits from Rees, whom he did not like and accused of poisoning him and "mesmerizing" him. Rees took part in the Nuremberg Trials of 1945.

Taken by surprise, Hitler had Hess' staff arrested. Questioning revealed that Hess was not motivated by disloyalty, but had simply cracked under the strain of the war. The official statement from the German government said that Hess had fallen victim to hallucinations brought on by old injuries from the previous war.

My coming to England in this way is, as I realise, so unusual that nobody will easily understand it. I was confronted by a very hard decision. I do not think I could have arrived at my final choice unless I had continually kept before my eyes the vision of an endless line of children's coffins with weeping mothers behind them, both English and German, and another line of coffins of mothers with mourning children.[24]

Hitler also stripped Hess of all of his party and state offices, and privately ordered him shot on sight if he ever returned to Germany. However, Hitler did grant Hess' wife a pension. Martin Bormann succeeded Hess as deputy under a newly-created title.

Trial and imprisonment

Hess was detained by the British for the remainder of the war, for most of the time at Maindiff Court Military Hospital in Abergavenny, Wales, where he would often be taken to the White Castle on Offa's Dyke Path. It was rumoured that he was befriended by the local populace.[25] He was also held just outside Lostwithiel in Cornwall for six months, in a large property aptly named 'Castle'. He then became a defendant at the Nuremberg Trials of the International Military Tribunal, where, in 1946, he was found guilty on two of four counts: crimes against peace (planning and preparation of aggressive war) and conspiracy with other German leaders to commit crimes. He was found not guilty of war crimes or crimes against humanity. He was given a life sentence.

Some of his last words before the tribunal were, "I regret nothing." For decades he was addressed only as prisoner number seven. Throughout the investigations prior to trial Hess claimed amnesia, insisting that he had no memory of his role in the Nazi Party. He went on to pretend not to recognise even Hermann Göring — who was as convinced as the psychiatric team that Hess had lost his mind. Hess then addressed the court, several weeks into hearing evidence, to announce that his memory had returned — thereby destroying his defence of diminished responsibility. He later confessed to having enjoyed pulling the wool over the eyes of the investigative psychiatric team.

Hess was considered to be the most mentally unstable of all the defendants. He would be seen talking to himself in court, counting on his fingers, laughing for no obvious reason. Such behaviour was a source of great annoyance to Göring, who made clear his desire to be seated apart from him. The request was denied.

Following the release in 1966 of Baldur von Schirach and Albert Speer, Hess was the sole remaining inmate of Spandau Prison, partly at the insistence of the Soviets. Guards reportedly said he degenerated mentally and lost most of his memory. For two decades, his main companion was warden Eugene K. Bird, with whom he formed a close friendship. Bird wrote a 1974 book titled The Loneliest Man in the World: The Inside Story of the 30-Year Imprisonment of Rudolf Hess about his relationship with Hess.

Frank Keller, a former guard at Spandau, said that "Hess would march by himself in the jail courtyard every day". Keller also said that Hess would march in the classic Nazi heel-to-toe style.

Many historians and legal commentators have opined that his long imprisonment was an injustice. In his book, The Second World War Part III, Winston Churchill wrote,

Reflecting upon the whole of the story, I am glad not to be responsible for the way in which Hess has been and is being treated. Whatever may be the moral guilt of a German who stood near to Hitler, Hess had, in my view, atoned for this by his completely devoted and frantic deed of lunatic benevolence. He came to us of his own free will, and, though without authority, had something of the quality of an envoy. He was a medical and not a criminal case, and should be so regarded.

Hess' flight raised suspicions with Soviet dictator Josef Stalin that secret discussions were under way between Great Britain and Germany to attack the Soviet Union. Later, in a meeting with Stalin, Churchill would address the topic and find Stalin still believed secret agreements were discussed with Hess. "When I make a statement of facts within my knowledge I expect it to be accepted," Churchill responded to Stalin, again denying that the incident resulted in any communications with Nazi Germany.[26]

In the early 1970s, the U.S., British and French governments had approached the Soviet government to propose that Hess be released on humanitarian grounds due to his age. The Soviet official response was apparently to reject these attempts and reportedly "refused to consider any reduction in Hess' life sentence."[27] U.S. President Richard Nixon was in favour of releasing Hess and stated that the U.S., Britain and France should continue to entreat the Soviet Union for his release.

In 1977, Britain's chief prosecutor at Nuremberg, Sir Hartley Shawcross, characterised Hess' continued imprisonment as a "scandal" [28] In 1987, the new Soviet leadership agreed that Hess should be set free on humanitarian grounds.

Death and legacy

On 17 August 1987, Hess died while under Four Power imprisonment at Spandau Prison in West Berlin, at the age of 93. He was found in a summer house in a garden located in a secure area of the prison with an electrical cord wrapped around his neck. His death was ruled a suicide by self-asphyxiation. He was buried at Wunsiedel in a Hess family grave plot sold to his family by the Vetters of the Sechsämtertropfen bitter liquor company of Wunsiedel. Spandau Prison was subsequently demolished to prevent it from becoming a shrine.[29][30]

After Hess' death, neo-Nazis from Germany and the rest of Europe gathered in Wunsiedel for a memorial march and similar demonstrations took place every year around the anniversary of Hess' death. These gatherings were banned from 1991 to 2000 and neo-Nazis tried to assemble in other cities and countries (such as the Netherlands and Denmark). Demonstrations in Wunsiedel were again legalised in 2001. Over 5,000 neo-Nazis marched in 2003, with over 9,000 in 2004, marking some of the biggest Nazi demonstrations in Germany since 1945. After stricter German legislation regarding demonstrations by neo-Nazis was enacted in March 2005, the demonstrations were banned again.

At the time of his death, he was the last surviving member of Hitler's cabinet.

Speculation

Flight to Britain

The Queen's Lost Uncle

Claims were made in The Queen's Lost Uncle, a television programme broadcast in November 2003 and March 2005 on Britain's Channel 4 that according to unspecified "recently released" documents, Hess flew to the UK to meet Prince George, Duke of Kent, who had to be rushed from the scene due to Hess' botched arrival. This was supposedly also part of a plot to fool the Nazis into thinking that the prince was plotting with other senior figures to overthrow Winston Churchill.

Lured into a trap?

In May 1943, the American Mercury magazine published a story from an anonymous source that indicated the British Secret Service lured Hess to Scotland. The article posited that Hess had come to Britain in the belief he would meet with the Duke of Hamilton, and that when he was intercepted by farmer David McLean, he admitted to home guardsmen that "he had come from Germany and was hunting the private aerodrome on the Duke of Hamilton's estate, ten miles away." The Duke was a member of the Anglo-German Fellowship Association. According to the source, British Secret Service agents had intercepted the correspondence to the Duke, which had been brought from Germany by an "eminent diplomat", and had begun responding in the Duke's name and handwriting. Thus encouraged, Hitler sent Hess to propose an accommodation that would reverse German gains in the west in exchange for a free hand in dealing with the Soviet Union in the east. This was a month before Germany attacked the Soviet Union, breaking their non-aggression/neutrality pact.

Hitler offered total cessation of the war in the West.Germany would evacuate all of France except Alsace and Lorraine, which would remain German. It would evacuate Holland and Belgium, retaining Luxembourg. It would evacuate Norway and Denmark. In short, Hitler offered to withdraw from Western Europe, except for the two French Provinces and Luxembourg, in return for which Great Britain would agree to assume an attitude of benevolent neutrality towards Germany as it unfolded its plans in Eastern Europe.[31]

Violet Roberts, whose nephew Walter was a close relative of the Duke of Hamilton and was working in the political intelligence and propaganda branch of the Secret Intelligence Service (SO1/PWE), was friends with Hess' mentor, Karl Haushofer. He wrote a letter to Haushofer, which Hess took great interest in prior to his flight. Haushofer replied to Violet Roberts, suggesting a post office box in Portugal for further correspondence. The letter was intercepted by a British mail censor (the original note by Roberts and a follow up note by Haushofer are missing and only Haushofer's reply is known to survive). Certain documents Hess brought with him to Britain were supposed to remain sealed until 2017. However, when the seal was broken in 1991-92, they were missing. Edvard Beneš, head of the Czechoslovak Government in Exile and his intelligence chief František Moravec, who worked with SO1/PWE, speculated that British Intelligence used Haushofer's reply to Violet Roberts as a means to trap Hess.[32]

The fact that the files concerning Hess will be kept closed to the public until 2016 allows the debate to continue, since without these files the existing theories cannot be tested. Hess was in captivity for almost four years of the war and thus he was absent from most of it, in contrast to the others who stood accused at Nuremberg. According to data published in a book about Wilhelm Canaris, a number of contacts between Britain and Germany were kept during the war.[33] It cannot be known, however, whether these were direct contacts on specific affairs or an intentional confusion created between secret services for the purpose of deception. Martin Allen's book about the background of the flight is based on forged documents in the British National Archives (see the article by E. Haiger).

Hess' parachute landing

After Hess' Bf 110 was detected on radar, a number of pilots were scrambled to meet it, but none made contact. (The tail and one engine of the Bf 110 can be seen in the Imperial War Museum in London; the other engine is on display at the National Museum of Flight in East Lothian).

Some witnesses in the nearby suburb of Clarkston claimed Hess' plane landed smoothly in a field near Carnbooth House. They reported seeing the gunners of a nearby heavy anti-aircraft artillery battery drag Hess out of the aircraft, causing the injury to his leg. The following night a Luftwaffe aircraft circled the area above Carnbooth House, possibly in an attempt to locate Hess' plane. It was shot down.

The witness accounts are said to uncover various insights. Hess' flight path implies that he was looking for the home of Duke of Hamilton and Brandon, a large house on the River Cart. Hess landed near Carnbooth House, the first large house on the River Cart, located to the west of Cynthia Marciniak's house, his presumed destination. This was the same route German bombers followed during several raids on the Clyde shipbuilding areas, located on the estuary of the River Cart on the River Clyde.

Murder conspiracy theories

Wolf Rüdiger Hess and Hess' Nuremberg lawyer Alfred Seidl claim that Hess was murdered by two MI6 agents in the garden of Spandau Prison. They point out that the prisoner was in very bad medical condition, even unable to do up his shoes because of arthritis in his fingers and needed regular help by his nurse. So, they say, Hess could technically never have strangled himself. Also, his suicide note was forged, they allege.[34] They point to the second autopsy, which the family insisted on, carried out by Munich forensic pathologists. In this autopsy, several errors of the British military's autopsy report were corrected, and the Munich doctors said that the marks around Hess' neck did not look like those found in a usual suicide by strangulation. However, Professor Dr. Wolfgang Spann,[35] who was in charge of the second autopsy publicly stated that "we can't prove a third hand participated in the death of Rudolf Hess".[36] Therefore, medical evidence for the murder theory is inconclusive.

In 2008 the Tunisian Abdallah Melaouhi, who acted as Hess' medical caretaker in Spandau prison from 1984 to 1987, was dismissed from his position in the advisory board for integration of his local German district parliament after he wrote a book titled I looked into the murderer's eyes in which he claimed that his patient was murdered by the British Intelligence Service.[37]

Prisoner at Spandau a double?

According to Dr. Hugh Thomas' book The Murder of Rudolf Hess (1979), the prisoner tried at Nuremberg and incarcerated in Spandau as Rudolf Hess was actually a double who was willingly impersonating him. Thomas examined the prisoner in 1973 as a physician of the British Army attached to Spandau Prison and writes that the man had no scarring that would indicate a bullet wound whatsoever. The real Hess was shot through the left lung, the bullet entering just above the left armpit and exiting between the spine and left shoulder blade, during World War I. This finding appeared to be confirmed when the prisoner's body was given two separate autopsies after his death in 1987 neither of which reported finding scarring that would indicate such a wound; however, when Hess' full medical records were released it was revealed that the bullet wound was in a different place than Thomas had claimed, and that scarring from the clean shot was likely to have been minimal.

In popular culture

Film and television

Rudolf Hess has been portrayed by the following actors in film, television and theater productions;[38]

- George Lynn in the 1943 United States short documentary film Plan for Destruction.

- Victor Varconi in the 1944 American film The Hitler Gang

- Carroll O'Connor in "Engineer of Death: The Eichmann Story", a 1960 episode of the American TV series Armstrong Circle Theatre

- Predrag Lakovic in the 1971 Yugoslavian television production Nirnberski epilog

- Wolfgang Lukschy played "Reinhard Holtz", a former Nazi and the sole prisoner of a Spandau-like prison in the 1975 United States film Inside Out

- Maurice Roëves in the 1982 American television production Inside the Third Reich

- Laurence Olivier in the 1985 American action film Wild Geese II

- Richard Edson in the 1997 American drama Snide and Prejudice

- Roc LaFortune in the 2000 Canadian/U.S. T.V. production Nuremberg

- James Babson in the 2003 Canadian/U.S. T.V. production Hitler: The Rise of Evil

- Conor Timmis in the 2004 American documentary Hitler's Lost Plan.

- André Hennicke in the 2005 German T.V. miniseries Speer und Er

- Victor Wagner in "Caso Mengele", a 2005 episode of the Brazillian TV series Linha Direta

- Ben Cross in the 2006 British/U.S. television production Nuremberg: Nazis on Trial

- Attila Harsányi in the 2008 Romanian theatre production The Ten Commandements of Rudolf Hess

- Shown and called by name in the Japanese anime Fullmetal Alchemist: The Conqueror of Shamballa

Literature

Rudolf Hess has been portrayed in literary works by the following authors;

- Upton Sinclair in his Lanny Budd Series

- Eric Knight in 1942 novel Sam Small Flies Again

- Timothy Findley in 1981 novel Famous Last Words

- Daniel Carney in 1982 novel The Square Circle

- Katherine Kurtz in 1992 novel The Lodge of the Lynx

- Peter Lovesey in 1992 novel The Secret of Spandau

- Greg Iles in 1993 thriller novel Spandau Phoenix

- Christopher Priest in the 2002 novel The Separation

- David Edgar in 2000 play Albert Speer

- Michael Moorcock in 2001 novel The Dreamthief's Daughter

- Peter Ho Davies in 2007 novel The Welsh Girl

- Ethan Mordden in 2008 novel The Jewcatcher

- In the 2006 alternate-history novel Farthing, by Jo Walton, Hess is not portrayed, but his flight is the story's divergence point with real history: his entreaties have been accepted, and have led to a peace between United Kingdom and Nazi Germany, and to the former withdrawing from World War II.

- Gary Manley in 2009 novel My Girlfriend is her Sister

Other

- Hess' symbolism to extremists is the central topic in Chumbawamba's song "On the Day the Nazi Died". It was covered by several artists, mainly from the anarcho-punk spectrum, like Across the Border or Stockholms Anarkafeministkör.

- In Joy Division's song "Warsaw", lyrics include reference to Hess' prison number, 31G-350125

- The British neo-nazi band Skrewdriver's songs "Prisoner Of Peace" and "Forty Six Years" are about Rudolf Hess. The first was released in 1985 and called for Hess to be freed. The second was released in 1988 and celebrated Hess' memory.

- The Chad Mitchell Trio's "The Twelve days of Christmas", released in 1964, parodies the Nazi party, mentioning Hess as the 2nd day gift: "Rudolph Hess' Blessings".

- The British pop group Spandau Ballet's name was derived from a Berlin lavatory scrawling, said to be a nickname for a form of suicide at Spandau Prison (hanging oneself); as Hess was the lone inmate of the prison at the time, they adopted the name he was synonymous with it.

References

Notes

- ↑ Maev Kennedy (28 September 2007). "How Nixon showed pity for 'the world's loneliest man' | World news". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,,2178948,00.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Milmo, Cahal (2007-09-28). "Russians persecuted Hess 'because he plotted against them' - This Britain, UK - The Independent". London: News.independent.co.uk. http://news.independent.co.uk/uk/this_britain/article3007142.ece. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Casciani, Dominic (2007-09-28). "UK | British sympathy for jailed Nazi". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/7017191.stm. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Day, Peter (2007-09-28). "Russia blocked UK plans to free Rudolf Hess". London: Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2007/09/28/whess128.xml. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Luke Baker (2007-09-28). "Life imprisonment of Nazi Hess a charade | Reuters". Uk.reuters.com. http://uk.reuters.com/article/topNews/idUKL2785983520070927. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "''"Neo-Nazis held for Oslo 'racist' murder.''" BBC, 29 January 2001". BBC News. 2001-01-29. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/1142780.stm. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Neo-Nazi bid to buy hotel in Rudolf Hess birthplace blocked." caterersearch.com 26 February 2007

- ↑ "Skinhead jailed for neo-Nazi lyrics in songs." The Scotsman, 13 May 2007

- ↑ Česky. "Ρούντολφ Ες (πολιτικός) - Βικιπαίδεια" (in (Greek)). El.wikipedia.org. http://el.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%CE%A1%CE%BF%CF%8D%CE%BD%CF%84%CE%BF%CE%BB%CF%86_%CE%95%CF%82_(%CF%80%CE%BF%CE%BB%CE%B9%CF%84%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C%CF%82)&oldid=1109889. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ The occult historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (2003: 114) now affirms Hess' membership in the Thule Society. It should be noted that Goodrick-Clarke had previously (1985: 149) maintained that Hess was no more than a guest to whom the Thule Society extended hospitality during the Bavarian revolution of 1918.

- ↑ Claus Hant, http://www.younghitler.com/, Young Hitler, London, 2010, p. 396

- ↑ Schwarzwaller, Wulf. Rudolf Hess The Last Nazi" ISBN# 0-915765-52-7

- ↑ "GERMANY: Mess's Successor". Time (magazine). 02 March 1942. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,773092,00.html. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ↑ Pennick, Nigel Hitler’s Secret Sciences:His Quest for the Hidden Knowledge of the Ancients New York:1982 C.W. Daniel Co., Ltd.

- ↑ Shirer, William L.. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

- ↑ Bird, Eugene K. (1974). Prisoner #7: Rudolf Hess. The Viking Press. p. 235. NOTE: Bird showed the Haushofer Letters in the National Archives in Washington D. C.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Galland, Adolf (1968 Ninth Printing - paperbound). The First and the Last: The Rise and Fall of the German Fighter Forces, 1938-1945. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 56.

- ↑ Olwen Hedley, Her Majesty's Tower of London, pp.19-20, Pitkin Pictorials Ltd., London, 1976

- ↑ Hedley, p.19

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Foley: Michael Smith, Hodder & Stoughton, 1999

- ↑ "Ian Fleming on Crowley as a spy". People.tribe.net. http://people.tribe.net/ionamiller/blog/e7ce4dc9-5570-4c6b-ae19-204452d95625. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Ross, Colin A. (1995). Satanic ritual abuse: principles of treatment. University of Toronto Press. p. 13. ISBN 0802073570.

- ↑ 10 June 1941 (from Rudolf Hess: Prisoner of Peace by his wife, Ilse Hess).

- ↑ "WW2 People's War - Marjorie's War". BBC. 2005-08-23. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/stories/40/a5279240.shtml. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Churchill, Winston, The Second World War, Vol. III, The Grand Alliance p. 49, Boston:1985 Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Interview with Bild am Sonntag, 10 April 1977. Quoted in: Wolf R. Hess, My Father Rudolf Hess, p. 402.

- ↑ "Hess Dies at 93; Hitler's Last Lieutenant". New York Times. 23 August 1987. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DEFDE1338F930A1575BC0A961948260. Retrieved 2007-07-21. "Walter Richard Rudolf Hess, the last of Hitler's lieutenants, died last week in Spandau Prison in West Berlin in characteristically murky circumstances. Allied officials said Hess had committed suicide, as did his long-dead fellow Nazis - Hitler, Goring, Goebbels and Himmler, strangling himself with an electric cord. They said he left a note pointing to suicide. But a lawyer for the partially blind 93-year-old prisoner suggested there might have been foul play."

- ↑ "Germany The Inmate of Spandau's Last Wish". Time (magazine). 31 August 1987. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,965331,00.html. Retrieved 2007-08-21. "Nearly every day for four decades, the prisoner took a stroll through a tiny garden inside West Berlin's forbidding Spandau fortress. He was never without a keeper and his gait had slowed to a shuffle over the years, but he rarely missed the opportunity for fresh air. Last Monday a guard left him alone briefly in a small cottage at the garden's edge. A few minutes later the guard returned to find the sole inmate of Spandau slumped over, an electrical cord wound tightly around his neck. Rushed to the nearby British Military Hospital, 93-year-old Hess was pronounced dead at 4:10 p.m. An autopsy showed that he had died of asphyxiation."

- ↑ "The Inside Story of the Hess Flight" The American Mercury compendium volume CX-CXI Spring 1974 page 18 p. 22

- ↑ McBlain and Trow (2000), "Hess: the British Conspiracy"

- ↑ Richard Basset (2005), "Hitler’s Spy Chief"

- ↑ Wolf Rudiger Hess/ Alfred Seidl: Who Murdered My Father Rudolf Hess? My Father's Mysterious Death in Spandau. Reporter Press, 1989

- ↑ BBC2 Newsnight, 28 February 1989

- ↑ Knopp, Guido. Hitler´s Henchmen. London, Sutton Publishers, 2000

- ↑ "Bezirk feuert Krankenpfleger von Heß" (in German). Bild (largest European newspaper). http://www.bild.de/BILD/berlin/aktuell/2008/07/24/bezirk-feuert-krankenpfleger-von/rudolf-hess.html.

- ↑ "Rudolf Hess (Character)". IMDb.com. http://www.imdb.com/character/ch0042374/. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

Bibliography

- Allen, Peter. The Crown and the Swastika: Hitler, Hess, and the Duke of Windsor.

- Brenton, Howard. H.I.D.: Hess Is Dead.

- Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War; Volume 3: The Grand Alliance (Cassell & Co., 1950)

- Cornell University Law Library - "Analysis of the Personality of Adolph Hitler" Cornell University lawschool. Readers can download a PDF version of the whole document

- Costello, John. Ten Days to Destiny: The Secret Story of the Hess Peace Initiative and British Efforts to Strike a Deal With Hitler. Also published as Ten Days That Saved the West.

- Douglas-Hamilton, James. Motive for a Mission: The Story Behind Rudolf Hess's Flight to Britain.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. The Occult Roots of Nazism: The Ariosophists of Austria and Germany 1890-1935. (Wellingborough, England: Aquarian Press, 1985, ISBN 0-85030-402-4)

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism and the Politics of Identity. (New York University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8147-3124-4. Paperback 2003, ISBN 0-8147-3155-4)

- Ernst Haiger Fiction, Facts, and Forgeries: The 'Revelations' of Peter and Martin Allen about the History of the Second World War. The Journal of Intelligence History, Vol 6 no. 1 (Summer 2006 [published in 2007]), pp. 105–117.

- Harris, John. Hess:The British Conspiracy

- Hess, Ilse. Prisoner of Peace.

- Hess, Rudolf. Selected speeches.

- Hess, Wolf Ruidger. My Father Rudolf Hess.

- Hutton, Joseph Bernard. Hess: The Man and His Mission.

- Irving, David John Cawdell. Hess: The Missing Years 1941–1945.

- Le Tissier, Tony. Farewell to Spandau.

- Knopp, Guido for ZDF Hitlers helfer - Hess, der Stellvertreter. (German TV, 1998, ISBN 0-7509-3781-5)

- Kilzer, Louis C. Churchill's Deception: The Dark Secret That Destroyed Nazi Germany.

- Leasor, James The Uninvited Envoy.

- Machtan, Lothar. The Hidden Hitler. (2001) ISBN 0-465-04308-9

- Manvell, Roger. Hess: A Biography.

- Moriarty, David M. Rudolf Hess, Deputy Führer: A Psychological Study.

- Nesbit, Roy Conyers, and Georges Van Acker. The Flight of Rudolf Hess: Myths and Reality.

- Padfield, Peter. Hess: Flight for the Führer.

- Padfield, Peter. Hess: The Führer's Disciple.

- Picknett, Lynn, Clive Prince, and Stephen Prior. Double Standards The Rudolf Hess Cover-Up. ISBN 0-7515-3220-7

- Pile, G. Rudolf Hess: Prisoner of Peace.

- Rees, John R., and Henry Victor Dicks. The Case of Rudolf Hess; A Problem in diagnosis and forensic psychiatry.

- Rees, Philip, editor. Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right Since 1890. (1991, ISBN 0-13-089301-3)

- Royce, William Hobart The Behest of Hess'.

- Smith, Alfred. Rudolf Hess and Germany's Reluctant War, 1939-41.

- Tuccille, Jerome, and Philip S. Jacobs. The Mission. (Dutton Adult, 1991 novel, ISBN 1-55611-199-1)

- Thomas, Hugh. The Murder of Rudolf Hess (republished as Hess: A Tale of Two Murders).

- Schwarzwäller, Wulf. Rudolf Hess, the Last Nazi. (A Zenith edition)

External links

- Rudolf Hess at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Article about British release of information about Hess' crash-landing outside Glasgow

- Rudolf Hess' relationship to Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy

- Correspondence on Rudolph Hess' incarceration held by the National Archives of the United Kingdom

- Mail firm issues stamps of Hitler deputy Reuters 22 May 2008

|

|||||||||||||||||